American Labor's Untold

Story

by Wm. Schmidt. -

www.tigersoft.com

Today, a young man actually came up to me and asked me what day it was!

I told him it was September 1st. It was Labor Day. It is the day we

should recall

the sacrifices of so many men and women who fought for the rights we now take for

granted: a 40 hour work week, decent pay, over-time pay, work-place safety,

limits on child-labor, the right to form a union for protection without

retailiation...

http://www.amazon.com/Labors-Untold-Story-Richard-Boyer/dp/0916180018

Now in its 3rd edition and 26th printing...

Years ago I read a book entitled Labor's Untold Story by Richard O. Buyer

and Herbert Morais. It should be required reading for anyone wanting to understand

American labor history and appreciate the huge sacrifices made for us by so many brave

and disenfrachised workers and union organizers. The rights we now take for

granted

did not spring easily forth from a beneficent government. They had to be fought for.

Capital

was ruthlessly opposed to them. It was indifferent to the plight of those they

exploited.

It believed that its profits depended on continued explotation.

Capital is still ready to abuse its power and run roughtshod over those it employs.

Perhaps, reading about these struggles from 1880 to 1942 here, will allow us to

see that we, too, must pick sides and struggle to achieve such basic human rights as

decent wages, safe working confitons, reasonable job security. retirement benefits,

affordable education and universal health care. If capital says that these goals are

too

expensive, tell them that too much money is wasted by paying CEOs tens of

millions of dollars in salaries and fraudulent bonuses. Tell them to stop the insane

$3 TRILLION WAR in Iraq and spend the savings here at home. Have them

understand the vast human potential this would release for constructive, rather

than destructive purposes Make them see that their biggest market is American

workers and their families. If American workers are not paid reasonably, a

Depression

will surely lie ahead.

The lyrics for "Which Side Are You On." by Florence Reese

Sung by Pete Seeger.

Come all of you good workers

Good news to you I'll tell

Of how that good old union

Has come in here to dwell

(Chorus)

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Our father was a union man.

Some day ill be one too.

The bosses fired daddy

What's a family gonna do?

(Chorus)

My daddy was a miner

And I'm a miner's son

And I'll stick with the union

Till every battle's won

(Chorus)

They say in Harlan County

There are no neutrals there

You'll either be a union man

Or a thug for J.H. Blair

(Chorus)

Oh, workers can you stand it?

Oh, tell me how you can

Will you be a lousy scab

Or will you be a man?

(Chorus)

Don't scab for the bosses

Don't listen to their lies

Us poor folks haven't got a chance

Unless we organize

(Chorus)

Other organizing songs - Union Maid sung

by Pete Seeger and Arlo Guthrie.

Solidarity

Forever by Pete Seeger

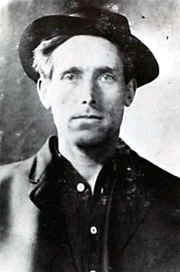

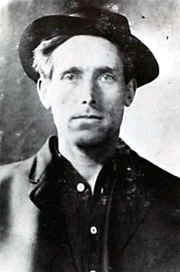

I Dreamed Joe Hill Last Night

sung by Joan Baez

Sacrifices of Organized

Labor

1806 The union of Philadelphia Journeymen Cordwainers was

convicted of and bankrupted by charges of criminal conspiracy after a strike for higher

wages, setting a precedent by which the U.S. government would combat unions for years to

come.

1825 The first strike for the 10-hour work-day occurred by

carpenters in Boston.

1835 Children employed in the silk mills in Paterson, NJ went on

strike for the 11 hour day/6 day week.

1860 800 women operatives and 4,000 workmen marched during a

shoemaker's strike in Lynn, Massachusetts.

1874 The original Tompkins Square Riot. As unemployed

workers demonstrated in New York's Tompkins Square Park, a detachment of mounted police

charged into the crowd, beating men, women and children indiscriminately with billy clubs

and leaving hundreds of casualties in their wake. Commented Abram Duryee, the Commissioner

of Police: "It was the most glorious sight I ever

saw..."

1877 U.S. railroad workers began strikes to protest wage

cuts.

1877 Ten coal-mining activists ("Molly Maguires")

were hanged in Pennsylvania.

1877 A general strike halted the movement of U.S. railroads.

In the following days, strike riots spread across the United States. The next week,

federal troops were called out to force an end to the nationwide strike. At the

"Battle of the Viaduct" in Chicago, federal troops

(recently returned from an Indian massacre) killed 30 workers and wounded over 100.

1884 - The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions,

forerunner of the AFL, passed a resolution stating that "8 hours shall constitute a

legal day's work from and after May 1, 1886." Though the Federation did not intend to

stimulate a mass insurgency, its resolution had precisely that effect. ( http://www.lutins.org/labor.html )

1886 - Haymarket Massacre - May Coordinated strikes and demonstrations are held

nationwide,

to demand an eight-hour workday for industrial workers. McCormick Reaper Works

factory strike; unarmed strikers,

police clash; several strikers are killed. A meeting of workingmen is held near

Haymarket Square; police arrive to "

disperse the peaceful assembly; a bomb is thrown into the ranks of the police; the police

open fire; workingmen

evidently return fire; police and an unknown number of workingmen killed; the bomb thrower

is unidentified. police

arrest anarchist and labor activists. The grand jury indicts 31, charged with being

accessories to the murder of policeman

Mathias J. Degan; eight are chosen to stand trial: Albert Parsons, August Spies, Oscar

Neebe, Louis Lingg, George Engel,

Adolph Fischer, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden. Jury selection commences; 981

citizens are questioned during

the voir dire process; the resultant panel of twelve are largely businessmen, clerks or

salesmen; the jurors, like the

public at large, hold preconceived notions about the defendants' connection to the

bombing. Trial testimony begins;

227 testify including 54 members of the Chicago Police Department and the defendants

Fielden, Schwab, Spies and Parsons;

the defendants are prosecuted not as perpetrators but as responsible for instigating the

violence; a guilty verdict and

death sentence are considered inevitable. The jury convicts the defendants and

sentences Neebe to fifteen years

in the penitentiary and the others to death by hanging. 1887 -- Illinois

Supreme Court upholds rulings and verdict.

November 2, 1887 -- The U.S. Supreme Court denies an appeal, despite an

international campaign for clemency.

Louis Lingg commits suicide in his jail cell. November 11, 1887 --

Albert Parsons,

August Spies, George Engel, Louis Lingg and Adolph Fischer were executed.

They had organized for an 8-hour day and were framed for their efforts.

( http://www.fullbooks.com/Labor-s-Martyrs.html

)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"If

you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement," Spies told the

judge,

"then hang us. Here you will tread upon a spark, but here, and there, and behind you,

and in front of

you, and everywhere, the flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put

it out.

The ground is on fire upon which you stand." ( http://members.tripod.com/~RedRobin2/index-54.html

)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

November 13, 1887 -- In Chicago,

the funeral procession of Lingg, Parsons, Spies, Engel, and Fischer in Chicago

is witnessed by 150,000 - 500,000 people. June 26, 1893 - Illinois governor John

Peter Altgeld pardons Neebe,

Fielden, and Schwab.

( http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ichihtml/hayhome.html

)

1892 - Strike in the Coeur d'Alene mining region of northern Idaho,

unionists discover a company plant,

Charles Siringo. Trouble ensues, with union men dynamiting a mill and capturing 130

non-union workers

and holding them prisoner in a union hall. Several persons are killed by gunfire. Over 400

union men

commandeer a train and take it to Wardner , Idaho, where they seize three mines, ejecting

non-union

workers and company officials. Governor Willey declares martial law and asks President

Benjamin

Harrison to send federal troops, which he does. The strike grew out of the mine owners'

decision to reduce

wages for certain workers from 35 cents an hour to 30 cents. Federal troops arrest

600 union men and

sympathizers, placing them in warehouses surrounded by 14-foot high fences. For two

months, the men

are kept without hearing or formal charges, then most are released. Union leaders are

tried.

1892 - Homestead Strike - lockout and strike which

began on June 30, 1892, culminating in a battle

between strikers and private security agents on July 6, 1892. It is one of the most

serious labor disputes

in U.S. history. The dispute occurred in the Pittsburgh-area

town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, between

the Amalgamated Association of Iron

and Steel Workers (the AA) and the Carnegie

Steel Company.

The AA was an American labor union formed in 1876. A craft union, it represented skilled iron and steel workers.

The AA's membership was concentrated in ironworks west of the Allegheny

Mountains. The union negotiated national

uniform wage scales on an annual basis; helped regularize working hours, workload levels

and work speeds;

and helped improve working conditions. It also acted as a hiring hall,

helping employers find scarce puddlers and rollers.[1]

The AA was an American labor union formed in 1876. A craft union, it represented skilled iron and steel workers.

The AA's membership was concentrated in ironworks west of the Allegheny

Mountains. The union negotiated

national uniform wage scales on an annual basis; helped regularize working hours, workload

levels and work

speeds; and helped improve working conditions. It also acted as a hiring hall,

helping employers find scarce puddlers

and rollers.[1]

With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire on June 30, 1892, Frick and the leaders

of the local AA union entered into negotiations in February. With the steel industry doing

well and prices higher,

the AA asked for a wage increase. Frick immediately countered with a 22 percent wage

decrease that would

affect nearly half the union's membership and remove a number of positions from the

bargaining unit. Carnegie

encouraged Frick to use the negotiations to break the union: "...the Firm has decided

that the minority must give

way to the majority. These works, therefore, will be necessarily non-union after the

expiration of the present

agreement."[11]

Frick then unilaterally announced on April 30, 1892

that he would bargain for 29 more days.

If no contract was reached, Carnegie Steel would cease to recognize the union. Carnegie

formally approved

Frick's tactics on May 4.[12]

Frick locked workers out of the plate mill

and one of the open hearth furnaces on the evening of June 28.

When no collective bargaining agreement was reached on June 29, Frick locked the

union out of the rest

of the plant. A high fence topped with barbed wire, begun in January, was completed and

the plant sealed to

the workers. Sniper towers with searchlights were constructed near each mill building, and

high-pressure

water cannons (some capable of spraying boiling-hot liquid) were placed at each entrance.

Various aspects

of the plant were protected, reinforced or shielded.[13]

At a mass meeting on June

30, local AA leaders reviewed the final negotiating sessions and announced

that the company had broken the contract by locking out workers a day before the contract

expired.

The Knights

of Labor, which had organized the mechanics and transportation workers at Homestead,

agreed

to walk out alongside the skilled workers of the AA. Workers at Carnegie plants in Pittsburgh, Duquesne,

Union Mills and Beaver Falls struck in sympathy the same day.[14]

The striking workers were determined to keep the plant closed. They secured a

steam-powered river launch

and several rowboats to patrol the Monongahela

River, which ran alongside the plant. Men also divided

themselves into units along military lines. Picket lines were thrown up around the plant

and the town, and 24-hour

shifts established. Ferries and trains were watched. Strangers were challenged to give

explanations for their presence

in town; if one was not forthcoming, they were escorted outside the city limits. Telegraph

communications with AA

locals in other cities were established to keep tabs on the company's attempts to hire

replacement workers. Reporters

were issued special badges which gave them safe passage through the town, but the badges

were withdrawn if it

was felt misleading or false information made it into the news. Tavern owners were even

asked to prevent excessive

drinking.[15]

Frick was also busy. The company placed ads for replacement workers in newspapers as

far away as Boston, St. Louis

and even Europe.[16]

But unprotected strikebreakers would be driven off. On July 4, Frick formally

requested that

Sheriff William H. McCleary intervene to allow supervisors access to the plant. Carnegie

corporation attorney

Philander Knox gave the go-ahead to the sheriff on July 5, and McCleary

dispatched 11 deputies to the town to

post handbills ordering the strikers to stop interfering with the plant's operation. The

strikers tore down the handbills

and told the deputies that they would not turn over the plant to nonunion workers. Then

they herded the deputies

onto a boat and sent them downriver to Pittsburgh.[17]

After consultations with Knox, Frick in April 1892 had contracted with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

to provide security at the plant. His intent was to open the works with nonunion men on July 6. Knox devised a plan

to get the Pinkertons onto the mill property. With the mill ringed by striking workers,

the agents would access the

plant grounds from the river. Three hundred Pinkerton agents assembled on the Davis Island

Dam on the Ohio

River about five miles below Pittsburgh at 10:30 p.m. on the night of July 5, 1892. They were given Winchester

rifles, placed on two specially-equipped barges and towed upriver.[18]

The strikers were prepared for them. The AA had learned of the Pinkertons as soon as

they had left Boston for

the embarkation point. The strikers blew the plant whistle at 2:30 a.m., drawing thousands

of men, women and

children to the plant. The small flotilla of union boats went downriver to meet the

barges. Strikers on the steam

launch fired a few random shots at the barges, then withdrew—blowing the launch

whistle to alert the plant.[19]

The Pinkertons attempted to land under cover of darkness about 4 a.m. A large crowd of

families had kept pace

with the boats as they were towed by a tug into the town. A few shots were fired at the

tug and barges, but no one

was injured. The crowd tore down the barbed-wire fence and strikers and their families

surged onto the Homestead

plant grounds. Some in the crowd threw stones at the barges, but strike leaders shouted

for restraint.[20]

The Pinkerton agents attempted to disembark. Conflicting testimony exists as to which

side fired the first shot.

According to unnamed and unidentified witnesses,[citation needed] Pinkertons shot

first. According to witnesses

who gave their names and identities, unionists shot first[21].

Frederick Heinde, captain of the Pinkertons, and William Foy, a worker, were both

wounded. The Pinkerton

agents aboard the barges then fired into the crowd, killing two and wounding 11. The crowd

responded in kind,

killing two and wounding 12. The firefight continued for about 10 minutes.[22]

The strikers then huddled behind the pig and scrap iron in the mill yard while the

Pinkertons cut holes in the side

of the barges so they could fire on any who approached. The Pinkerton tug departed with

the wounded agents,

leaving the barges stranded. The strikers soon set to work building a rampart of steel

beams further up the riverbank

from which they could fire down on the barges. Hundreds of women continued to crowd on the

riverbank between

the strikers and the agents, calling on the strikers to 'kill the Pinkertons'.[23]

The strikers continued to sporadically fire on the barges. Union members took potshots

at the ships from their

rowboats and the steam-powered launch. The burgess of Homestead, John McLuckie, issued a proclamation at

6:00 a.m. asking for townspeople to help defend the peace; more than 5,000 people

congregated on the hills

overlooking the steelworks. A 20-pounder brass cannon was set up on the shore opposite the

steel mill, and an

attempt was made to sink the barges. Six miles away in Pittsburgh, thousands of

steelworkers gathered in the streets,

listening to accounts of the attacks at Homestead; hundreds, many of them armed, began to

move toward the town

to assist the strikers.[24]

The Pinkertons attempted to disembark again at 8:00 a.m. A striker high up the

riverbank fired a shot. The

Pinkertons returned fire, and four more strikers were killed (one by shrapnel sent flying

when cannon fire hit one

of the barges). Many of the Pinkerton agents refused to participate in the firefight any

longer; the agents crowded

onto the barge farthest from the shore. More experienced agents were barely able to stop

the new recruits from

abandoning the ships and swimming away. Intermittent gunfire from both sides continued

throughout the morning.

When the tug attempted to retrieve the barges at 10:50 a.m., gunfire drove it off. More

than 300 riflemen positioned

themselves on the high ground and kept a steady stream of fire on the barges. Just before

noon, a sniper shot

dead another Pinkerton agent.[25]

After a few more hours, the strikers attempted to burn the barges. They seized a raft,

loaded it with oil-soaked

timber and floated it toward the barges. The Pinkertons nearly panicked, and a Pinkerton

captain had to threaten

to shoot anyone who fled. But the fire burned itself out before it reached the barges. The

strikers then loaded a

railroad flatcar with drums of oil and set it afire. The flatcar hurtled down the rails

toward the mill's wharf where

the barges were docked. But the car stopped at the water's edge and burned itself out.

Dynamite was thrown at

the barges, but it only hit the mark once (causing a little damage to one barge). At 2:00

p.m., the workers poured

oil onto the river, hoping the oil slick would burn the barges; attempts to light the

slick failed.[26]

The AA worked behind the scenes to avoid further bloodshed and defuse the tense

situation. At 9:00 a.m.,

outgoing AA international president William Weihe rushed to the sheriff's office and asked

McCleary to

convey a request to Frick to meet. McCleary did so, but Frick refused. He knew that the

more chaotic the

situation became, the more likely it was that Governor Robert

E. Pattison would call out the state militia.[27]

Sheriff McCleary resisted attempts to call for state intervention until 10 a.m. on July 7. In a telegram to

Gov. Pattison, he described how his deputies and the Carnegie men had been driven off, and

noted that the

mob was nearly 5,000-strong. Pattison responded by requiring McCleary to exhaust every

effort to restore

the peace. McCleary asked again for help at noon, and Pattison responded by asking how

many deputies

the sheriff had. A third telegram, sent at 3:00 p.m., again elicited a response from the

governor exhorting

McCleary to raise his own troops.[28]

At 4:00 p.m., events at the mill quickly began to wind down. More than 5,000 men—most

of them armed

mill hands from the nearby South Side, Braddock and Duquesne works—arrived at the

Homestead plant.

Weihe urged the strikers to let the Pinkertons surrender, but he was shouted down. Weihe

tried to speak again.

But this time, his pleas were drowned out as the strikers bombarded the barges with

fireworks left over from

the recent Independence Day celebration. Hugh O'Donnell,

a heater in the plant and head of the union's strike

committee, then spoke to the crowd. He demanded that each Pinkerton be charged with

murder, forced to turn

over his arms and then be removed from the town. The crowd shouted their approval.[29]

The Pinkertons, too, wished to surrender. At 5:00 p.m., they raised a white flag and

two agents asked to

speak with the strikers. O'Donnell guaranteed them safe passage out of town. As the

Pinkertons crossed

the grounds of the mill, the crowd formed a gauntlet through which the agents passed. Men

and women

threw sand and stones at the Pinkerton agents, spat on them and beat them. Several

Pinkertons were clubbed

into unconsciousness. Members of the crowd ransacked the barges, then burned them to the

waterline.[30]

As the Pinkertons were marched through town to the Opera House (which served as a

temporary jail), the

townspeople continued to assault the agents. Two agents were beaten as horrified town

officials looked on.

The press expressed shock at the treatment of the Pinkerton agents, and the torrent of

abuse helped turn media

sympathies away from the strikers.[31]

The strike committee met with the town council to discuss the handover of the agents to

McCleary. But the

real talks were taking place between McCleary and Weihe in McCleary's office. At 10:15

p.m., the two

sides agreed to a transfer process. A special train arrived at 12:30 a.m. on July 7.

McCleary, the international

AA's lawyer and several town officials accompanied the Pinkerton agents to Pittsburgh.[32]

But when the Pinkerton agents arrived at their final destination in Pittsburgh, state

officials declared that they

would not be charged with murder (as per the agreement with the strikers) but rather

simply released.

The announcement was made with the full concurrence of the AA attorney. A special train

whisked the

Pinkerton agents out of the city at 10:00 a.m. on July 7.[33]

On July 7, the strike committee sent a telegram to Gov. Pattison to attempt to persuade

him that law and order

had been restored in the town. Pattison replied that he had heard differently. Union

officials traveled to Harrisburg"

and met with Pattison on July

9. Their discussions revolved not around law and order, but the safety of the

Carnegie plant.[34]

Pattison, however, remained unconvinced by the strikers' arguments. Although Pattison

had ordered the

Pennsylvania militia to muster on July 6, he had not formally charged it with doing

anything. Pattison's refusal to

act rested largely on his concern that the union controlled the entire city of Homestead

and commanded the

allegiance of its citizens. Pattison refused to order the town taken by force, for fear a

massacre would occur.

But once emotions had died down, Pattison felt the need to act. He had been elected with

the backing of a

Carnegie-supported political machine, and he could no longer refuse to protect Carnegie

interests.[35]

The steelworkers resolved to meet the militia with open arms, hoping to establish good

relations with the troops.

But the militia managed to keep its arrival in the town a secret almost to the last

moment. At 9:00 a.m. on July

12,

the Pennsylvania state militia arrived at the small Munhall train station near the

Homestead mill (rather than the

downtown train station as expected). More than 4,000 soldiers surrounded the plant. Within

20 minutes they

had displaced the picketers; by 10:00 a.m., company officials were back in their offices.

Another 2,000 troops

camped on the high ground overlooking the city.[36]

The company quickly brought in strikebreakers and restarted production under the

protection of the militia.

Despite the presence of AFL pickets in front of several recruitment offices across the

nation, Frick easily found

employees to work the mill. The company quickly built bunk houses, dining halls and

kitchens on the mill grounds

to accommodate the strikebreakers. New employees, many of them black, arrived on July 13, and the mill

furnaces

relit on July 15. When

a few workers attempted to storm into the plant to stop the relighting of the furnaces,

militiamen fought them off and wounded six with bayonets.[37]

The company could not operate for long with strikebreakers living on the mill grounds,

and permanent replacements had to be found.

Legal retaliation against the strikers proved to be the most promising avenue for the

company. On July 18, 16

of the strike leaders were charged with conspiracy, riot and murder. Company lawyer Knox

drew up the charges on behalf of state authorities. Each man was jailed for one night and

forced to post a $10,000 bond. The union retaliated by charging company executives with

murder as well. The company men, too, had to post a $10,000 bond, but they were not forced

to spend any time in jail. The same day, the town was placed under martial law, further

disheartening many of the strikers.[39]

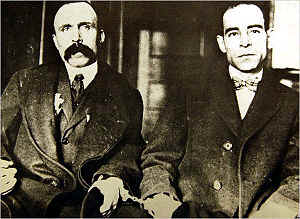

National attention became riveted on Homestead when, on July 23, Alexander

Berkman, an anarchist, gained

entrance to Frick's office, shot him twice in the neck and then stabbed him twice with a

knife. Berkman was

convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 22 years in prison.[40]

The Berkman incident prompted the final collapse of the strike. Hugh O'Donnell, without

consulting his colleagues on the strike committee, offered what amounted to unconditional

surrender to the company

Additional legal ammunition against the strikers was levied in the fall. Knox had engaged

in ex parte

communication with Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chief Justice

Edward Paxson. Knox submitted charges to Paxson which accused all 33 members of the strike

committee with treason under the state's Crimes Act of 1860. In Pittsburgh for the court's

fall term, Paxson (after conferring with Knox once more) issued the treason charges

himself on August 30.

A $500,000 bond was required. Most of the men could not raise the money, and went to jail

while awaiting trial; a few simply went into hiding. Legal scholars were outraged by clear

abuse of the law, and deeply concerned by Paxson's apparently biased behavior. State

prosecutors, worried by the flimsy nature of the charges, declined to prosecute.[42]

Support for the strikers evaporated. The AFL refused to call for a boycott of Carnegie

products in September 1892. Wholesale crossing of the picket line occurred, first among

Eastern European immigrants and then among all workers. The strike had collapsed so much

that the state militia pulled out on October 13, ending the 95-day occupation. The AA was nearly

bankrupted by the job action. Nearly 1,600 men were receiving a total of $10,000 a week in

relief from union coffers. With only 192 out of more than 3,800 strikers in attendance,

the Homestead chapter of the AA voted, 101 to 91, to return to work on November 20, 1892.[43]

In the end, only four workers were ever tried on the actual charges filed on July 18.

Three AA members were found innocent of all charges. Hugh Dempsey, the leader of the local

Knights of Labor District Assembly, was found guilty of conspiring to poison nonunion

workers at the plant—despite the state's star witness recanting his testimony on the

stand. Dempsey served a seven-year prison term. In February 1893, Knox and the union agreed

to drop the charges filed against one another, and no further prosecutions emerged from

the events at Homestead.[44

The Homestead strike broke the AA as a force in the American labor movement. Many

employers refused to

sign contracts with their AA unions while the strike lasted. ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homestead_Strike

)

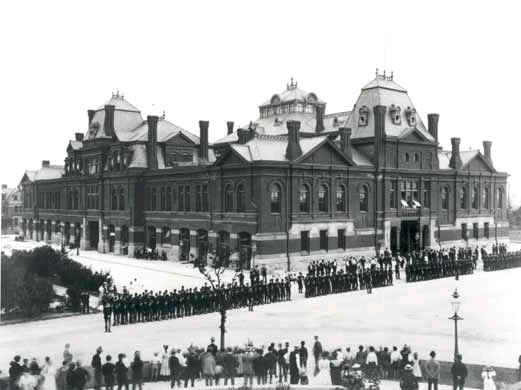

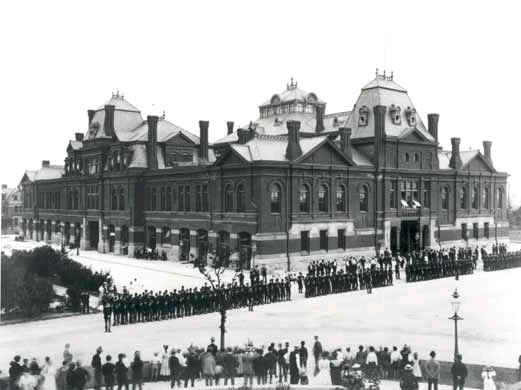

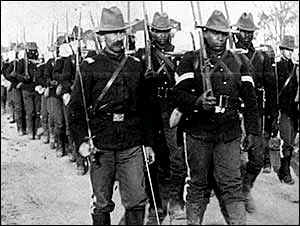

Illinois

National Guard can be seen guarding the building during the Pullman During Railroad Strike

in 1894.

1894 - 2,000 federal troops were called into Pullman, Ill.,

to break up a huge

strike against the Pullman railway company and two workers were shot and

killed by U.S. deputy marshals. The Pullman Strike occurred when 4,000 Pullman Palace

Car

Company workers reacted to a 28% wage cut by going on a wildcat strike

in Illinois on May 11, 1894, bringing

traffic west of Chicago to a halt. George Pullman

was a "welfare capitalist." Firmly believing that labor

unrest

was caused by the unavailability of decent pay and living conditions, he paid

unprecedented wages and built a

company town

by Lake Calumet

called Pullman in what is now the southern part of the city. George Pullman

was a "welfare capitalist." To reduce labor unrest , he paid

unprecedented wages and built a company town by

Lake Calumet

called Pullman in what is now the southern part of the city

During the economic panic of 1893, the Pullman Palace Car Company cut wages as

demands for their

train cars plummeted and the company's revenue dropped. A delegation of workers complained

that

the corporation that operated the town of Pullman didn't decrease rents, but Pullman

"loftily declined to talk with them."[3]

Many of the workers were already members of the American

Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs,

which supported their strike by launching a boycott in which union members refused to run

trains containing

Pullman cars. The strike effectively shut down production in the Pullman factories and led

to a lockout.

Railroad workers across the nation refused to switch Pullman cars (and subsequently Wagner Palace cars)

onto trains. The ARU declared that if switchmen were disciplined for the boycott, the

entire ARU would strike

in sympathy.[3]

The boycott was launched on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on

twenty-nine railroads

had quit work rather than handle Pullman cars.[3]

Adding fuel to the fire the railroad companies began hiring

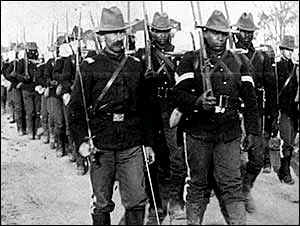

replacement workers (that is, strikebreakers), which only increased hostilities. Many African

Americans,

fearful that the racism expressed by the American

Railway Union would lock them out of another labor

market crossed the picket line to break the strike, adding a racially charged tone to the

conflict.[4]

On June 29, 1894, Debs hosted a peaceful gathering to obtain support for the strike

from fellow

railroad workers at Blue Island, Illinois. Afterward groups within the crowd became

enraged and set fire

to nearby buildings and derailed a locomotive. Elsewhere in the United States, sympathy

strikers prevented

transportation of goods by walking off the job, obstructing railroad tracks or threatening

and attacking

strikebreakers. This increased national attention to the matter

and fueled the demand for federal action.[5]

The railroads were able to get Edwin Walker, general counsel for the Chicago, Milwaukee

and St. Paul Railway,

appointed as a special federal attorney with responsibility for dealing with the strike.

Walker obtained an

injunction barring union leaders from supporting the strike and demanding that the

strikers cease their activities

or face being fired. Debs and other leaders of the ARU ignored the injunction, and federal

troops were called

into action.[6]

The strike was broken up by United States Marshals and some 12,000 United

States Army troops, commanded

by Nelson Miles, sent in by President Grover

Cleveland on the premise that the strike interfered with the delivery

of U.S. Mail, ignored a federal injunction and

represented a threat to public safety. The arrival of the military led

to further outbreaks of violence. During the course of the strike, 13 strikers were killed

and 57 were wounded.

An estimated 6,000 rail workers did $340,000 worth of property damage (about $6,800,000

adjusted for inflation

to 2007). Debs was then tried for, and eventually found guilty of violating the

court injunction, and was sent to

prison for six months.[7]

A national commission formed to study causes of the 1894 strike found

Pullman's

paternalism partly to blame and Pullman's company town to

be "un-American." In 1898, the Illinois Supreme

Court forced the Pullman Company to divest ownership in the town, which was annexed to

Chicago.

Federal troops frequently

were needed in Idaho, 1892 and 1899. Federal troops frequently

were needed in Idaho, 1892 and 1899.

Miners in Idaho fought mine owners and their private militias. The Western

Federation of Miners

was created in the wake of the 1892 episode of violence, where miners are arrested and

imprisoned;

and while they were in federal prison, they talked about what has happened to them, and

they

decided they never wanted that to happen to them again, and they created the union.

With tragic consequences, the Governor and local officials paid little attention to

workers'

complaints of dangerous mining conditions and low pay and sided with the mine owners'

dogma that "private property" was the most important concern.

1899 - Union miners plant 60 boxes of dynamite

beneath the world's largest concentrator,

owned by the Bunker Hill Mining Company in Wardner, Idaho, and at 2:35 p.m. light the

fuse,

destroying the concentrator and several nearby buildings. Governor

Steunenberg calls upon

President McKinley to send federal troops to suppress the unrest. Federal troops

arrest

"every male--miners, bartenders, a doctor, a preacher, even a postmaster and a school

superindentent--" in the union-controlled town of Burke, Idaho. The men are loaded

into

boxcars, taken to Wardner, and herded into an old barn. Within a few days, the number

of men held captive in Wardner grows to over 1, 000.

1902

- Anthracite

Coal Strike

1904 - In the midst of a violent labor dispute, a railroad

depot in Independence, Colorado is

bombed, presumably under orders from the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners,

killing

fourteen non-union miners.

1905 - Idaho: Returning to his home in Caldwell from a walk

shortly after six p.m..

Frank Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho, is blown ten

feet in the air by a

bomb blast as he opens his gate and dies soon afterwards. Later, a waitress at the

Saratoga Hotel in Caldwell reports that a guest, Thomas Hogan, had trembling hands and

downcast eyes when she waited on his table shortly after the explosion. A search of

Hogan's

room turns up traces of plaster of paris in his chamber pot. Plaster of paris was the

substance

used to hold pieces of the bomb together. January 1, 1906: Thomas Hogan, also

known as

Harry Orchard, is arrested while having a drink at the Saratoga Bar and is charged with

the

first degree murder of Steunenberg. January 7, 1906: The state of Idaho hires

America's

most famous detective, James McParland of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, to head the

investigation of Steunenberg's assassination. He arrives in Boise two days later.

January 22, 1906: McParland meets Orchard in the state penitentiary and suggests

that more lenient treatment might be possible if were willing to turn state's evidence

against those who recruited him to commit his crime. February 1, 1906: Harry Orchard,

after breaking down several times and crying, completes a 64-page confession to the

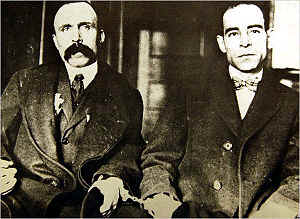

Steunenberg assassination and 17 other killings, all ordered, he says, by the inner

circle of the Western Federation of Miners, including William Haywood, Charles Moyer,

and George Pettibone. February 15, 1906: Governor McDonald of Colorado issues

a

warrant for the arrest of Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone. February 17, 1906:

Late at night, Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone are arrested in Denver and temporarily

housed in a local jail. February 18, 1906: Denied an opportunity to call

lawyers or

loved ones, the three union leaders are placed on a special train at daybreak. Orders are

issued that the train not stop until it has crossed the Idaho border.

April, 1906: The Supreme Court of Idaho rules that it has no jurisdiction to hear the

complaint of Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone that they were denied an opportunity

to fight extradition to Idaho. November, 1906: William Haywood loses his race

as

the Socialist Party candidate for Governor of Colorado. December 3,

1906: The Supreme

Court of the United States, with one dissent, rules that the union leaders' arrest and

forcible removal from Colorado, even though accomplished through the fraud and

connivance of leaders of two states, violated no constitutional rights of the defendants.

1907: Adams repudiates his confession and is transferred to Wallace, Idaho to stand

trial for an 1899 murder. The jury is unable to reach a verdict. Hayward an

Pettibone

are also acquitted by juries and the charges against Charles Moyer are dropped. 1908:

Harry Orchard is tried and convicted of the murder of Gov.

Steunenberg. He is sentenced

to death, but his sentence is commuted to life in prison.

(Source: http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/haywood/HAY_CHRO.HTM

1909 - NYC - 30,000 garment workers go on on strike.

As young as age 15, they are

worked seven days

a week, from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. (53 hour work week) with a half-hour lunch

break. During the busy season, the work was nearly non-stop. They were paid about $6

per week.

In some cases, they were required to use their own needles, thread, irons and occasionally

their own sewing machines. Owners hired thugs to break up striking women. Police

back

the owners and arrest strkers. Judges quickly sentenced them to Labor

Camps. One judge

said their strike went against God's will.

( http://www.aflcio.org/aboutus/history/history/uprising_fire.cfm

)

March 25, 1911, a Saturday, a fire broke out on

the top floors of the Triangle Shirtwaist

factory. Firefighters arrived at the scene, but their ladders weren’t tall enough to

reach the upper

floors of the 10-story building. Trapped inside because the owners had locked the fire

escape exit

doors, workers jumped to their deaths. In a half an hour, the fire was over, and 146

of the 500 workers—mostly young women—were dead...After the fire, their story

inspired hundreds of

activists across the state and the nation to push for fundamental reforms. For some,

such as

Frances Perkins, who stood helpless watching the factory burn, the tragedy inspired a

lifetime of advocacy for workers’ rights. She later became secretary of labor

under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Company owners were charged with

seven counts of manslaughter – but were found

not guilty. The incident was a turning point in labor law, especially concerning health

and safety.

For three days prior, the company, along with other warehouse owners, had grouped together

to

fight the Fire Commissioner's order that fire sprinklers be installed.

Mother Jones and Workers seeking to

organize a union.

She

sometimes took jobs in factories to understand the problems of workers,

or lived with them in tents. The workers

often were immigrants who spoke little

English and had no knowledge of how to

improve their lives in America. She gave

inspiring speeches that boosted their

spirits, or she held educational meetings.

Sometimes

she was a volunteer, sometimes she was paid for her work.

In 1877, working among railroad workers

in Pittsburgh, she organized her first

strike. In 1890, she took a job as an

organizer for the United Mine Workers.

In 1902, she led a march of coal miners'

wives against strikebreakers in

Pennsylvania. The next year, she led

"the march of the mill children"

from Pennsylvania to Long Island to protest child labor.

In 1912, at age 82, she endured arrest

and trial to fight for striking coal miners

in West Virginia. During the strike,

shooting had erupted between the miners

and guards hired to protect substitute

workers. Martial law was declared.

When Mother Jones went to Charleston, the

capital, to meet the governor,

she was arrested. A military prosecutor

indicted her and 47 others on the union

side -- none of the guards were charged

-- with conspiracy to commit murder.

( http://www.dailypress.com/topic/ny-sbp_62503x,0,6512878.story

)

1912 -

Lawrence, Mass. strikers' victory parade.

1912 - Lawrence

Textile Strike - A strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts

in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World. Work in a

textile mill takes place at a grueling pace. The labor is repetitive, and dangerous.

A number of children under the age of fourteen worked in the mills. Conditions

had grown even worse for workers in the decade before the strike. The introduction

of the two-loom system in the woolen mills lead to a dramatic speedup in the pace

of work. The increase in production enabled the factory owners to cut the wages

of their employees and lay off large numbers of workers. Those who kept their jobs

earned less than $9.00 a week for nearly sixty hours of work. The workers in

Lawrence

lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families

sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans;

as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the

Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the

children".

The mortality

rate for children was fifty percent by age six; thirty-six out of every

100 men and women who worked in the mill died by the time they reached twenty-five.

Prompted by one mill owner's decision to lower wages when a new law shortening

the workweek went into effect in January, the strike spread rapidly through the town,

growing to more than twenty thousand workers at nearly every mill within a week.

The strike, which lasted more than two months and which defied the assumptions

of conservative unions within the American Federation of Labor that immigrant,

largely female and ethnically divided workers could not be organized.

When Polish women weavers at Everett Cotton Mills realized that their employer had

reduced their pay by thirty two cents they stopped their looms and left the mill,

shouting

"short pay, short pay!" Workers at other mills joined the next day; within

a week more

than 20,000 workers were on strike.

Joseph

Ettor of the IWW had been organizing in Lawrence for some time before the strike;

he and Arturo Giovannitti of the IWW quickly assumed leadership of

the strike, forming a

strike committee made up of two representatives from each ethnic group in the mills,

which took responsibility for all major decisions. The committee, which arranged for

its

strike meetings to be translated into twenty-five different languages, put forward a

set of

demands; a fifteen percent increase in wages for a fifty-four-hour work week, double

time

for overtime work, and no discrimination against workers for their strike activity.

The City responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first

time in its history;

the Mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. The strikers

responded

with mass picketing. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in

front of

the mills, they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of

windows. The

court sentenced thirty-six workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge

stated, "The

only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences". The governor

then ordered

out the state militia and state police. Mass arrests followed.

A local undertaker and a member of the Lawrence school board

attempted to frame the strike leadership

by planting dynamite in several locations in town a week after the strike began. He was

fined $500

and released without jail time. William Wood, the owner of the American Woolen Company,

who had

made a large payment to the defendant under unexplained circumstances shortly before the

dynamite

was found, was not charged.

The authorities later charged Ettor and Giovannitti with murder for the death of striker Anna LoPizzo,[1]

likely

shot by the police. Ettor and Giovannitti had been three miles away, speaking to another

group of workers

at the time. They and a third defendant, who had not even heard of either Ettor or

Giovannitti at the time

of his arrest, were held in jail for the duration of the strike and several months

thereafter. The authorities

declared martial law, banned all public meetings and called out twenty-two more militia

companies to patrol

the streets.

The IWW responded by sending Bill Haywood, Elizabeth

Gurley Flynn and a number of other organizers

to Lawrence. The union established an efficient system of relief committees, soup

kitchens, and food distribution

stations, while volunteer doctors provided medical care. The IWW raised funds on a

nation-wide basis to provide

weekly benefits for strikers and dramatized the strikers' needs by arranging for several

hundred children to go to

supporters' homes in New York City for the duration of the strike. When city

authorities tried to prevent another

hundred children from going to Philadelphia on February 24 by

sending police and the militia to the station to

detain the children and arrest their parents, the police began clubbing both the children

and their mothers while

dragging them off to be taken away by truck; one pregnant mother miscarried. The press,

there to photograph

the event, reported extensively on the attack.

The public assault on the children and their mothers sparked a national outrage. Congress

convened investigative

hearings, eliciting testimony from teenaged workers who described how they had to pay for

their drinking water

and to do unpaid work on Saturdays. Helen

Herron Taft, the wife of President Taft,

attended the hearings; Taft later

ordered a nationwide investigation of factory conditions.

The national attention had an effect: the owners offered a five percent pay raise on March 1; the workers

rejected it. American Woolen Company agreed to all the strikers' demands on March 12, 1912. The rest

of the

manufacturers followed by the end of the month; other textile companies throughout New England,

anxious to

avoid a similar confrontation, followed suit. The children who had been taken in by

supporters in New York

City came home on March

30.

Ettor and Giovannitti remained in prison even after the strike ended. Haywood

threatened a general strike

to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill

gates". The IWW raised $60,000

for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in

their support; the authorities

in Boston, Massachusetts arrested all of the members of the

Ettor-Giovannitti Defense Committee. Fifteen

thousand Lawrence workers went on strike for one day on September 30 to

demand that Ettor and Giovannitti

be released. Swedish and French workers proposed a boycott of woolen goods from the United

States and a refusal

to load ships going to the U.S.; Italian supporters of Giovannitti rallied in front of the

United States consulate in Rome.

In the meantime, Ernest Pitman, a Lawrence building contractor who had done extensive

work for the American

Woolen Company, confessed to a district attorney that he had attended a meeting in the

Boston offices of Lawrence

textile companies where the plan to frame the union by planting dynamite had been made.

Pitman committed suicide

shortly thereafter when subpoenaed to testify. Wood, the owner of the American Woolen

Company, was formally

exonerated.

When the trial of Ettor, Giovannitti, and a co-defendant accused of firing the shot

that killed the picketer, began in

September 1912 in Salem, Massachusetts before Judge Joseph F.

Quinn, the three defendants were kept in metal

cages in the courtroom. Witnesses testified without contradiction that Ettor and

Giovannitti were miles away while

Caruso, the third defendant, was at home eating supper at the time of the killing.

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month

trial. Joe Ettor stated:

- Does the District Attorney believe that the gallows or

guillotine ever settled an idea?

If an idea can live, it lives because history adjudges it right. I ask only for justice. .

. .

The scaffold has never yet and never will destroy an idea or a movement. . . .

An idea consisting of a social crime in one age becomes the very religion of humanity in

the next. . . .

Whatever my social views are, they are what they are. They cannot be tried in this

courtroom..

All three defendants were acquitted on November 26, 1912.

The strikers, however, lost nearly all of the gains they had won in the next few years.

The IWW disdained written

contracts, holding that such contracts encouraged workers to abandon the daily class

struggle. In fact, however,

the mill owners had more stamina for that fight and slowly chiseled away at the

improvements in wages and

working conditions, while firing union activists and installing labor spies to keep an eye

on workers. A

depression in the industry, followed by another speedup, led to further layoffs. The IWW

had, by that time,

turned its attention to supporting the silk industry workers in Paterson,

New Jersey. The Paterson strike

ended in defeat.

( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_textile_strike

)

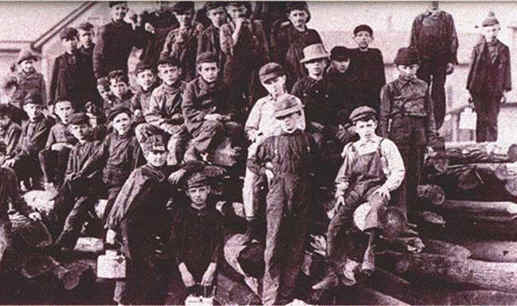

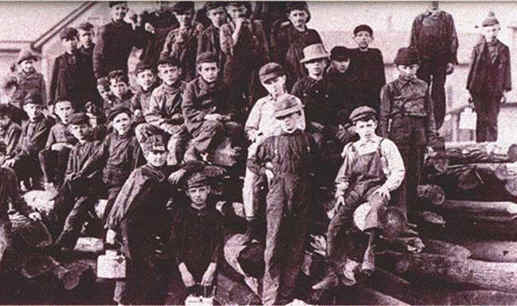

1913-14 - Calumet, Michigan

Copper Strike. Strike called by Western Federation of Miners

because mine owners would not recognize the union. Boys 12 years old worked in

the mine. Murder,

assault, intimidation followed. strikers demanded that two men be involved in the

operation of all equipment

for the sake of worker safety, demands for an 8 hour work day instead of 12 hours,

recognition of the union,

a minimum wage of $3 for underground workers, and a pay increase of 35 cents per day for

all surface workers.

WFM claimed nine thousand members in the region, with 98% of them voting in favor of the

strike. sheriff of

Houghton County, James Cruse, ontracted men from the Waddell-Mahon agency of New York.

These strike

breakers were well known to the WFM, having been involved in other strikes supported by

the union in the

western U.S. Waddell-Mahon men, as well as Ascher detectives, were also hired. Mine

owners refused to

recognize WFM and tried to use strike breakers (scabs)to start up mines.

Local newsapers refused to tell

the miners' side of strike, blaming them for all acts of violence.

The strike had started in July. It was not settled by the end of the year. At a

Christmas Party of 500

hundred miners's families, someone yelled "fire". In the ensuing melee

seventy-three people (including

fifty-nine children) were killed. There was no fire. To date it has not been established

who cried "fire"

and why. The most common theory is that "fire" was called out by the anti-union

company management

to disrupt the party. It was also claimed that the doors has been bolted shut by scabs.

The companies' anti union organziation, Citizens Allianc, sought to have Charles

Moyer, president of the

Western Federation of Miners, publicly exonerate

the Alliance of all fault in the tragedy. Moyer refused.

Rather than provide such an exoneration, Moyer announced that the Alliance was responsible

for the

catastrophe, claiming that an Alliance agent yelled the word “fire”.[3]

The Alliance assaulted Moyer in

nearby Hancock,

shot and kidnapped

him. They placed him on a train with instructions to leave the state

and never return. After getting medical attention in Chicago (and holding a press conference where he

displayed his gunshot wound) he returned to Michigan to continue the work of the

WFM.

( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_Hall_Disaster

http://www.hu.mtu.edu/vup/Strike/background3.html.

)

1914 - Ludlow, Colorado Massacre

- This was the most violent labor conflict in U.S. history;

the reported death toll was nearly 200 It began withe deaths of 20 people, 11

of them children,

during an attack by the Colorado National Guard on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal

miners and their

families at Ludlow, Colorado in the U.S. on April 20, 1914.

These deaths occurred after a day-long fight

between strikers

and the Guard. Two women, twelve children, six miners and union officials and one

National Guardsman were killed. In response, the miners armed themselves and attacked

dozens of

mines, destroying

property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard.

This was the bloodiest event in the 14-month 1913-1914 southern Colorado Coal

Strike. The strike

was organized by the United Mine Workers of America

(UMWA) against coal

mining companies in Colorado. The three biggest mining companies were the Rockefeller

family-owned

Colorado Fuel & Iron

Company (CF&I), the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company (RMF), and the Victor-American

Fuel Company (VAF)

Mining firms had long been able to attract low-skill labor, in spite of modest wages and stiff cost-cutting

policies designed to maintain profits

in a competitive industry. This made conditions in the mines difficult and

often dangerous for the workers, and the sector became a ripe target for union organizers.

Colorado miners

had attempted to periodically unionize since the state's first strike in

1883.

The Western Federation of Miners organized primarily

hard rock miners in the gold and silver camps

during the 1890s. Beginning in 1900, the UMWA began organizing coal

miners in the western states,

including southern Colorado. The UMWA decided to focus on the CF&I because of the

company's

harsh management tactics under the conservative and distant Rockefellers

and other investors. As part of their

campaign to break or prevent strikes, the coal companies had lured immigrants, mainly

from southern

and

Eastern

Europe and Mexico.

CF&I's management purposely mixed immigrants of different nationalities

in the mines to discourage communication that might lead to organization.

As was typical in the industry of that day, miners were paid by tons of coal mined and

not reimbursed for

"dead work," such as laying rails, timbering, and shoring the mines to make them

operable. Given the

intense pressure to produce, mine safety was often given short shrift. More than 1,700

miners died in

Colorado from 1884 to 1912, a rate that was between 2 and 3.5 times the national average

during

those years. Furthermore, the miners felt they were being short-changed on the weight of

the coal they

mined, arguing that the scales used for paying them were different from those used for

coal customers.

Miners challenging the weights risked being dismissed.

Most miners also lived in "company towns," where homes, schools, doctors, clergy, and

law enforcement

were provided by the company, as well as stores offering a full range of goods that could

be paid for in

company currency, scrip.

However, this became an oppressive environment in which law focused on

enforcement of increasing prohibitions on speech

or assembly by the miners to discourage union-building

activity. Also, under pressure to maintain profitability, the mining companies steadily

reduced their investment

in the town and its amenities while increasing prices at the company store so that miners

and their families

experienced worsening conditions and higher costs. Colorado's legislature had

passed laws

to improve the

condition of the mines and towns, including the outlawing of the use of scrip, but these

laws were poorly enforced.

Despite attempts to suppress union activity, secret organizing continued by the UMWA in

the years leading

up to 1913. Once everything had

been laid out according to their plan, the UMWA presented, on behalf

of coal miners, a list of seven demands:

- - Recognition of the union as bargaining agent

- - An increase in tonnage rates (equivalent to a 10% wage increase)

- - Enforcement of the eight-hour work day law

- - Payment for "dead work" (laying track, timbering, handling impurities, etc.)

- - Weight-checkmen elected by the workers (to keep company weightmen honest)

- - The right to use any store, and choose their boarding houses

and doctors

- - Strict enforcement of Colorado's laws (such as mine safety rules, abolition of scrip),

and an end to the dreaded company guard system

The major coal companies rejected the demands and in September 1913, the UMWA called a

strike.

Those who went on strike were promptly evicted from their company homes, and they moved to

tent villages

prepared by the UMWA, with tents built on wood platforms and furnished with cast iron

stoves on land leased

by the union in preparation for a strike.

In leasing the tent village sites, the union had strategically selected locations near

the mouths of the canyons,

which led to the coal camps for the purpose of monitoring traffic and harassing

replacement workers. Confrontations

between striking miners and replacement workers, referred to as "scabs" by

the union, often got out of control,

resulting in deaths. The company hired the Baldwin-Felts

Detective Agency to help break the strike by protecting

the replacement workers and otherwise making life difficult for the strikers.

Baldwin-Felts had a reputation for aggressive strike breaking. Agents shone searchlights on the tent villages

at night and randomly fired into the tents, occasionally killing and maiming people. They

used an improvised

armored car, mounted with a M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun that the union

called the "Death Special,"

to patrol the camp's perimeters. The steel-covered car was built in the CF&I plant in Pueblo

from the chassis

of a large touring sedan. Because of frequent sniping on the tent colonies, miners dug

protective pits beneath

the tents where they and their families could seek shelter.

On October 28,

as strike-related violence mounted, Colorado

governor Elias M. Ammons, called in the

Colorado National Guard. At first, the guard's appearance calmed the situation. But the

sympathies of the

militia leaders were quickly seen by the strikers to lie with company management. Guard

Adjutant General John

Chase had served during the violent Cripple Creek strike 10 years earlier, and

imposed a harsh regime in Ludlow.

|On March 10, 1914, the body of a replacement

worker was found on the railroad tracks near Forbes.

The National Guard believed that the man had been murdered by the strikers. Chase ordered

the Forbes

tent colony destroyed in retaliation. The attack was carried out while the Forbes colony

inhabitants were

attending a funeral of infants who had died a few days earlier. The attack was witnessed

by a young

photographer, Lou Dold, whose images of the

destruction appear often in accounts of the strike.

The strikers persevered until the spring of 1914. By then, the state had run out of

money to maintain the guard,

and was forced to recall them. The governor and the mining companies, fearing a breakdown

in order,

left two guard units in southern Colorado and allowed the coal companies to finance a

residual militia, which

consisted largely of CF&I camp guards in National Guard uniforms.

On the morning of April

20, the day after Easter was celebrated by the many Greek immigrants at Ludlow,

three Guardsmen appeared at the camp ordering the release of a man they claimed was being

held against his will.

This request prompted the camp leader, Louis Tikas, born in Crete, to meet with a local militia commander

at the train station in Ludlow village, a half mile (0.8 km) from the colony. While this

meeting was progressing,

two companies of militia installed a machine gun on a ridge near the camp and took a

position along a rail route

about half a mile south of Ludlow. Anticipating trouble, Tikas ran back to the camp. The

miners, fearing for the

safety of their families, set out to flank the militia positions. A firefight soon broke

out.

he fighting raged for the entire day. The militia was reinforced by non-uniformed mine

guards later in the afternoon.

At dusk, a passing freight train stopped on the tracks in front of the Guards'

machine gun placements,

allowing many of the miners and their families to escape to an outcrop of hills to the

east called the "Black Hills."

By 7:00 p.m., the camp was in flames, and the militia descended on it and began to search

and loot the camp.

Louis Tikas had remained in the camp the entire day and was still there when the fire

started. Tikas and two

other men were captured by the militia. Tikas and Lt. Karl Linderfelt, commander of one of two Guard companies,

had confronted each other several times in the previous months. While two militiamen held

Tikas, Linderfelt broke

a rifle butt over his head. Tikas and the other two captured miners were later found shot

dead. Their bodies lay

along the Colorado and Southern tracks for three days in full view of passing trains. The

militia officers refused

to allow them to be moved until a local of a railway union demanded the bodies be taken

away for burial.

During the battle, four women and eleven children had been hiding in a pit beneath one

tent, where they were

trapped when the tent above them was set on fire. Two of the women and all of the children

suffocated. These

deaths became a rallying cry for the UMWA, who called the incident the "Ludlow

Massacre."[1]

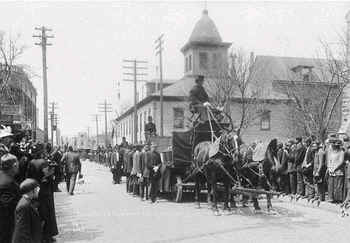

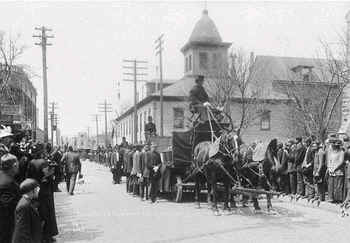

Coffins are marched

through Trinidad, Colorado, at the funeral for victims of the Ludlow massacre

In addition to the fire victims, Louis Tikas and the other men who were shot to death,

three company guards

and one militiaman were also killed in that day's fighting.

n response to the Ludlow massacre, the leaders of organized labor in Colorado issued a call to arms,

urging union members to acquire "all the arms and ammunition legally available,"

and a large-scale guerrilla war

ensued, lasting ten days. In Trinidad, Colorado, UMW officials openly distributed arms

and ammunition to strikers

at union headquarters. Believing their women and children to have been "wantonly

slaughtered" by the militia,

700 to 1,000 inflamed strikers "attacked mine after mine, driving off or killing the

guards and setting fire to the

buildings." At least fifty people, including those at Ludlow, were killed in ten days

of fighting against mine guards

and hundreds of militia reinforcements rushed back into the strike zone. The fighting

ended only when U.S.

President Woodrow

Wilson sent in federal troops.[2] The

troops disarmed both sides (displacing, and often

arresting, the militia in the process) and reported directly to

Washington.

The UMWA finally ran out of money, and called off the strike on December 10, 1914.

In the end, the strikers failed to obtain their demands, the union did not obtain

recognition, and many striking

workers were replaced by new workers. Over 400 strikers were arrested, 332 of whom were

indicted for

murder. Only one man, John Lawson, leader of the strike, was convicted of murder, and that

verdict was

eventually overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court. Twenty-two National Guardsmen,

including 10 officers,

were court-martialed.

All were acquitted, except Lt. Linderfelt, who was found guilty of assault for his attack

on Louis Tikas. However, he was given only a light reprimand.

The UMWA eventually bought the site of the Ludlow tent colony in 1916. Two years later,

they erected

the Ludlow

Monument to commemorate those who had died during the strike. .A company union was

established by John Rockerfeller, Jr. ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludlow_massacre

)

1916 - Everett (WA) Massacre

- On May 1, 1916 the Everett Shingle Weavers Union went on strike.

Strike-breakers had beaten the picketers, and the police did not get

involved, on the grounds that the mill

was on private property. At the end of the shift, the picketers

retaliated, but this time the police intervened,

IWW public speakers protested the unequal treatment. Realizing that

arrest alone did not serve as a deterrent

to the speakers, the police now began beating the speakers the

arrested. They ran I.W.W. members out of town,

and prohibited entrance to town, merely for being members. The

I.W.W. began bringing members to town in

groups, but the police (enlisting the aid of citizen-deputies) beat the

groups, as well. The worst of these beatings

was on October 30, 1916. Forty-one I.W.W. members had come by ferry to

Everett, to speak at Hewitt and

Wetmore. The Sheriff and his deputies beat these men, took them to Beverly

Park, and forced them to run

through a gauntlet of 'law and order' officials, armed with clubs and whips.

It was this horrific incident which

caused the I.W.W. to organize a group of 300 men to travel to Everett on

November 5 for a free-speech rally.

Five workers were killed. Thirty wounded. Nearly 300 were arrested,

. ( http://content.lib.washington.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/pnwlabor&CISOPTR=10&CISOSHOW=195

)

On November 5, 1916,

about 300 members of the IWW met at the IWW hall in Seattle

and then marched down

to the docks where they boarded the steamers Verona and Calista

which then headed north to Everett.

Verona arrived at Everett before Callista and as they

approached the dock in the early afternoon, the Wobblies

sang their fight song Hold the Fort. Local business interests,

knowing the Wobblies were coming, placed

armed vigilantes on the dock and on at least one tugboat in the harbor,

Edison, owned by the American

Tug Boat Company.[2] As

with previous labor demonstrations, the local business had also secured the aid

of law enforcement, including the Snohomish County sheriff Donald

McRae, who had targeted Wobblies for

arbitrary arrests and beatings.[3]

At the end of the mayhem, 2 citizen deputies lay dead with 16[9] or 20

others wounded, including Sheriff McRae.

The IWW officially listed 5 dead with 27 wounded, although it is

speculated that as many as 12 IWW members

may have been killed. There was a good likelihood that at least some of

the casualties on the dock were caused

not by IWW firing from the steamer, but on vigilante rounds from the

cross-fire of bullets coming from the

Edison.[10] The

local Everett Wobblies started their street rally anyway, and as a result, McRae's

deputized

citizens rounded them up and hauled them off to jail.[11] As a result of the shootings, the governor of the State of

Washington sent companies of militia to Everett and Seattle to help maintain

order.[12]

Upon returning to Seattle,

74 Wobblies were arrested as a direct result of the "Everett

Massacre" including IWW leader Thomas H. Tracy.

They were taken to the Snohomish County jail in Everett and charged with

murder of the 2 deputies. After a

two-month trial, Tracy was acquitted by a jury on May 5, 1917. Shortly

thereafter, all charges were dropped

against the remaining 73 defendants and they were released from jail.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Everett_massacre

)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Historians Philip Taft and Philip Ross have pointed out in their

comments on violence in labor history

that

"IWW activity was virtually free of violence... It is of some interest to note that a

speaker who

advocated

violence at a meeting at the IWW hall in Everett [Washington] was later exposed as a

private

detective."[13]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As a result, over 200 vigilantes or "citizen deputies", under the ostensible

authority of Snohomish County Sheriff McRae,

met in order to repel the "anarchists". As the Verona drew into the dock, and

someone on board threw a line over a

bollard, McRae stepped forward and called out "Boys, who's your leader?" The IWW

men laughed and jeered,

replying "We're all leaders," and they started to swing out the gang plank.

McRae drew his pistol, told them he was

the sheriff, he was enforcing the law, and they couldn't land here. There was a silence,

then a Wobbly came up to

the front and yelled out "the hell we can't."[4]

Just then a single shot rang out, followed by about ten minutes of intense gunfire.

Most of it came from the vigilantes

on the dock, but some fire came from the Verona, although the majority of the

passengers were unarmed.[5].

Whether the first shot came from boat or dock was never determined. Passengers aboard the Verona

rushed

to the opposite side of the ship, nearly capsizing the vessel. The ship's rail broke as a

result and a number of passengers

were ejected into the water, some drowned as a result but how many is not known, or

whether persons who'd

been shot also went overboard.[6] Over

175 bullets pierced the pilot house alone, and the captain of the Verona,

Chance Wiman, was only able to avoid being shot by ducking behind the ship's safe.[7]

Once the ship righted herself somewhat after the near-capsize, some slack came on the

bowline, and Engineer

Shellgren put the engines hard astern, parting the line, and enabling the steamer to

escape. Out in the harbor,

Captain Wiman warned off the approaching Calista and then raced back to Seattle.[8]

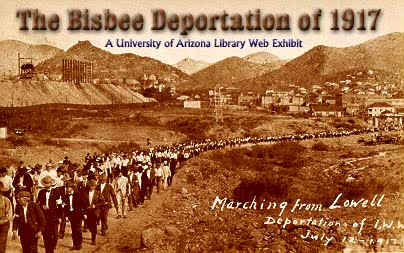

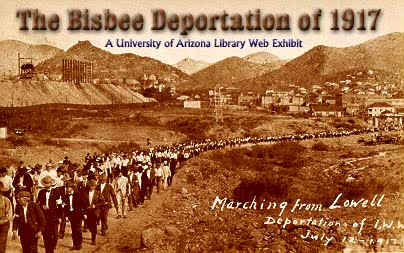

1917 - Bisbee Copper Mine Deportation

- 1,185 other men were herded into filthy boxcars by an

armed vigilante force in Bisbee, Arizona, and abandoned across the New Mexico border.

During World

War I, the price of copper reached unprecedented heights and the companies reaped enormous

profits. By

March of 1917, copper sold for $.37 a pound; it had been $.13 1/2 at the outbreak of World

War I in 1914.

With five thousand miners working around the clock, Bisbee was booming. To maintain

high production levels,

the pool of miners was increased from an influx of southern European immigrants. Although

the mining

companies paid relatively high wages, working conditions for miners were no

better than before the copper

market crash in 1907-1908. Furthermore, the inflation caused by World War I increased

living expenses and

eroded any gains the miners had realized in salaries. The mining companies

controlled Bisbee, not only

because they were the primary employers but because local businesses depended heavily on

the mines and

miners to survive. Even the local newspaper was owned by one of the major mining

companies, Phelps Dodge.

Prior to 1917, union activity had repeatedly been stifled. Between 1906 and 1907, for

example, about 1,200

men were fired for for supporting a union. Conversely, the Bisbee Industrial Association,

an alliance that was

pro-company and anti-union, was easily organized around the same time.

On June 24, 1917, the I.W.W. presented the Bisbee mining companies with a list of demands.

These

demands included improvements to safety and working conditions, such as requiring two men

on each

machine and an end to blasting in the mines during shifts. Demands were also made to end

discrimination

against members of labor organizations and the unequal treatment of foreign and minority

workers.

Furthermore, the unions wanted a flat wage system to replace sliding scales tied to the

market price

of copper. The copper companies refused all I.W.W. demands, using the war effort as

justification.

As a result, a strike was called, and by June 27 roughly half of the Bisbee work force was

on strike.

The Citizen's Protective League, an anti-union organization formed during a previous labor

dispute,

was resurrected by local businessmen and put under the control of Sheriff Harry Wheeler. A

group of

miners loyal to the mining companies also formed the Workman's Loyalty League. On July 11,

secret meetings of these two so-called "vigilante groups" were held to discuss

ways to deal with the

strike and the strikers.

The next day, starting at 2:00 a. m., calls were made to Loyalty Leaguers as far away as

Douglas,

Arizona. By 5:00 a. m., about 2,000 deputies assembled. All wore white armbands

to distinguish

them from other mining workers. No federal or state officials were notified of the

vigilantes' plans.

The Western Union telegraph office was seized, preventing any communication to the town.

At 6:30 a. m., Sheriff Harry Wheeler gave orders to begin the roundup. Throughout

Bisbee, men were roused

from their beds, their houses, and the streets. Though armed, the vigilantes were

instructed to avoid violence.

However, reports of beatings, robberies, vandalism, and abuse of women later surfaced.